In this essay, we argue that eco-labels on fuel dispensers are needed, as well as climate change and health warning labels. We also present evidence that they are potentially effective and will be well received. Social psychologist Stylianos Syropoulos has contributed to this part of the text.

In July 2022, Bloomberg News posed a question: Where are all the climate warning labels on gas pumps?[1] While there are at least 206 countries or jurisdictions that demand health information labels on cigarette packs[2], the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the only jurisdiction that demands climate and health warnings on gas pumps.[3] Sweden is the only country that requires eco-labels on fuel dispensers and some charging stations, displaying climate impact, renewable share, and raw materials.[4]

In 2020, experts in public health, climate and behavioral change demanded such labels on all points of sale of fossil fuels in an op-ed in The BMJ.[5]

By themselves, labels cannot be expected to substantially reduce the use of fossil fuels. They should be seen as part of a wide array of moves that reinforce each other.[6] Apart from measures aimed at raising consumer awareness and changing views and norms, like labelling and rules for advertising, economic means of control and regulations are also needed.

Lessons from efforts to curb smoking

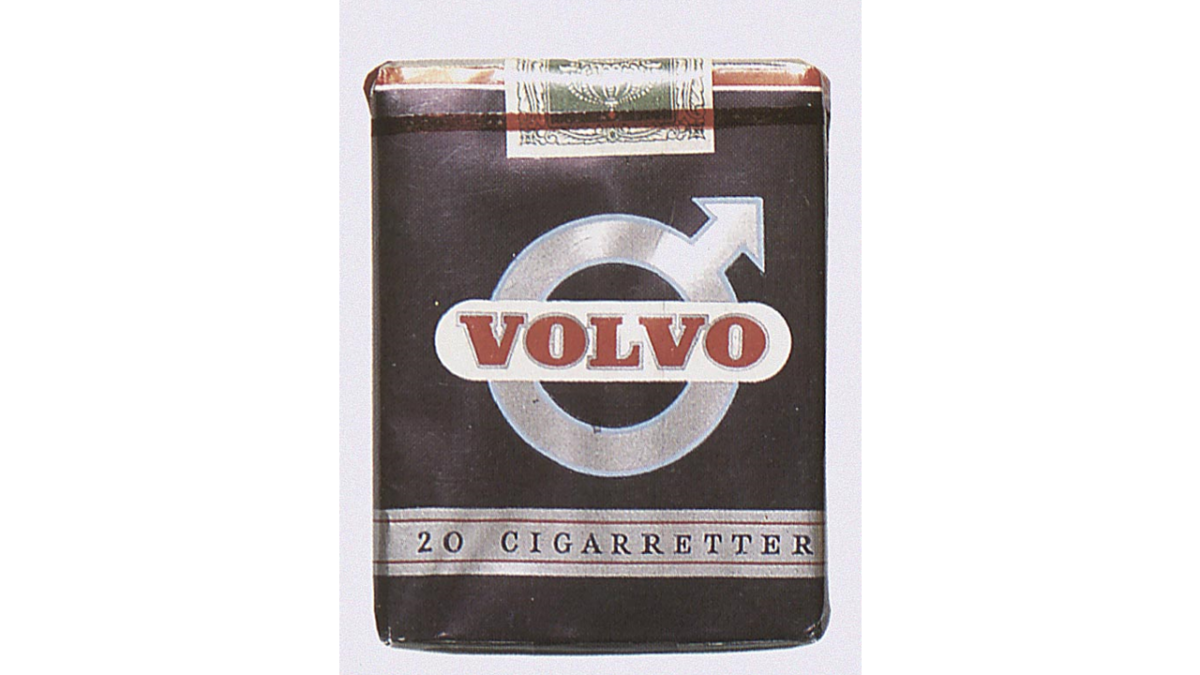

Such an array of measures carried fruit to curb smoking. In Sweden, health warning labels and tables of contents on cigarette packs became mandatory in 1977. Tobacco advertising is banned since 1993. A law on tobacco taxation came into force in 1994. The taxes have been gradually increased since then. From 1997, it is prohibited to sell tobacco to people younger than 18 years. Larger pictorial warning labels were introduced in 2002. Since 2005, it is not allowed to smoke in restaurants or indoor spaces used for public transit, among other places.

In the 1960s, half of the male Swedish population smoked daily. Today, the share is five percent. Consequently, the incidence of lung cancer among men has decreased 40 percent since 1980.

For Swedish women, the trajectories are lagging. Smoking increased until the 1970s, before starting to decline in the 1980s. The lung cancer incidence therefore rose at least until 2015. The prevalence is set to decline, since the share of female daily smokers has continued to decrease up until today, falling to six percent in 2022.

The trajectories for the use of fossil energy and its negative consequences are lagging even more. The reason is simple: the countermeasures are falling behind – or are yet to be introduced.

Soft measures are missing

The first measures to tackle the negative consequences of burning fossil energy concerned the reduction of air pollution from road vehicles. These measures were, in part, due to innovative sparks that flew across the Atlantic between Sweden and the USA. In the seventies the Swedish car manufacturer Volvo invented the so called three-way catalytic converter, which removes 90 percent of the nitrogen oxides from exhaust emissions. Thanks to this invention, California was able to introduce tough emission regulations in 1977. More American states followed, and since 1981 such catalytic converters are found in all new petrol cars in the USA. This inspired Swedish lawmakers, and since 1989 these converters are installed in all new petrol cars in Sweden. The EU introduced corresponding exhaust emission regulations in 1992. These regulations have been tightened ever since on both sides of the Atlantic.

Even so, outdoor air pollution prematurely kills more than four million people each year, and pollution from traffic is still severe in many cities.[7] Therefore, just as smoking is banned in some public spaces, old combustion engine cars are banned in Paris. Stockholm will only allow electric and biomethane cars in parts of the city centre from 2025.

Measures to combat greenhouse gas emissions from road vehicles were not introduced until the 2000s, even though the consequences of uncurbed climate change are vast, not only for the environment, but also for public health, society, and economy. The burning of fossil transportation fuels gives rise to about 30 percent of all emissions in the USA and in Sweden, and 20 percent worldwide.

So far, measures to reduce the climate impact of traffic amount to economic means of control like CO2-taxes, or regulations like mandated reductions of the average tailpipe CO2-emission from new cars. The same goes for the moves to reduce air pollution.

Measures aimed at raising awareness and changing social norms are still largely absent, in contrast to the case of smoking. It is an untapped resource.

Stronger case for fuel labels than tobacco labels?

It can be argued that such soft measures should be given a more prominent role to reduce the use of fossil fuels than they did to reduce smoking. Fossil energy still fulfils a crucial need in society, whereas tobacco does not. Therefore, no harm is done if tobacco taxes are drastically increased, or smoking is banned in all public places. In contrast, such draconic measures may disrupt society when applied to fossil energy. They risk ripping away public support from the cause to combat climate change and may give rise to political backlash. Measures aiming at sensitizing people are smoother and more flexible in that respect. Warning labels and eco-labels on points of sale of fossil fuels are examples of such measures.

The case for both warning labels and eco-labels

The recent European Tobacco Products Directive introduced larger pictorial warnings, but removed tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide information altogether, to avoid the false impression that products with lower levels of these substances and emissions are acceptable from a health point of view.[8]

In contrast, if we must use some amount of fossil fuels, biofuels, or electricity, it is meaningful to be able to choose between better or worse alternatives to minimize their damage. In other words, it is reasonable to give product information a larger role on labels intended for fuels than on labels intended for tobacco, thus releasing the consumer power to steer the market in a sustainable direction.

We argued that measures like fossil fuel labelling, which aim to sensitize people, must be seen as an integrated part of a wider array of moves. These should not only include ‘sticks’ like taxes, regulations, and warnings that suppress the use of fossil energy, but also ‘carrots’ that facilitate sustainable alternatives that the sensitized citizens can turn to. Eco-labels can point to such alternatives, if they are present on all fuels intended for road vehicles, including renewable electricity, renewable hydrogen, and sustainable biofuels like locally produced biomethane made of waste and residues.

For these reasons, we consider both warning labels and eco-labels on fuel dispensers to be worthwhile and look upon them as complementary.

Potential effects

Will labels on fuel dispensers make any difference? It is hard to disentangle the effect of health information labels on cigarette packs from that of other steps that successfully curbed smoking, even though the evidence suggests a positive effect.[9] It is even harder at this point to determine the effect of gas pump labelling, since it is present in just one city and one country, and these labels have only been up for a couple of years.

Preliminary studies of the US population (total N = 900) initiated by Think Beyond the Pump and performed by social psychologist Stylianos Syropoulos found that the perceived effectiveness of warning labels such as those in Cambridge, MA, to increase awareness about the negative consequences of burning gasoline is around 40–55 on the scale 0–100.

Two opinion polls in 2014 and 2016, before eco-labels were introduced in Sweden, found that no less than 70 percent of the adult Swedish population would probably select fuel based on its country of origin if that information is given (total N = 2000).[10]

Although extant research on the effectiveness of climate labels installed on fuel dispensers is limited, we can draw on research stemming from other domains to gain insights on the potential effectiveness of such labels.

In the context of the labels in Cambridge, MA, James Brooks and Kristie L. Ebi reviewed scholarship on efficacy of carbon and health warning labels.[11] The analysis revealed that climate and health information labels on gas pumps may activate climate concern norms and shift public opinion toward long term support of sustainable transportation emissions policies and practices.

Research on the effectiveness of labels that warn against the risks of smoking suggests that countries that have implemented such labels display a significantly higher level of knowledge of the associated dangers of smoking.[12] In fact, integrative analyses of 35 longitudinal investigations of the effectiveness of warning labels found that they significantly increase quit intentions and perceived harms from smoking.[13] Crucially, the majority of the warning labels included a visual, which has been theorized to be more effective at communicating risk. Indeed, evidence suggests that labels with a graphing component appear to be more effective at deterring smoking.[14]

Although there is a plethora of promising results about the effectiveness of cigarette warning labels, research on climate labels has been considerably more scarce. However, despite this lack of evidence, the premise of the effectiveness of such labels do not seem far-reaching for several reasons.

First, other labels that focus on the impact of certain behaviours on climate change have proven effective at curtailing the target behaviour. This goes, for example, for warning labels on meat meals.[15] Similarly, in the case of eco-labels, a recent review in Nature finds evidence that carbon labelling may affect consumer behaviour.[16] It may also influence producers, but more research is needed.

Second, these labels embody a lot of the established psychological mechanisms that are driving sustainable behaviour.[17] Among them are increased perceptions of trust, higher perceived efficacy for one’s actions, and effective communication of norms. In fact, research more broadly suggests that policy signals (i.e., actions taken by the government that signal support for a cause) are effective mechanisms of behaviour change.[18] Other potential mechanisms activated from climate labels on gas pumps include eliciting emotions that can inhibit unsustainable behaviours (e.g., guilt) or emotions that are linked to sustainable behaviour (e.g., hope).

Public support

Climate labels on fuel dispensers could be potentially widely supported because recent large-scale surveys with representative population data suggest that at least 70 percent of individuals in the United States, a country in which politicization of climate change discourse[19], and polarization of attitudes on the issue is high[20], are supportive of actions to limit CO2 in the atmosphere, and actions to increase renewable energy applications in day-to-day life.[21]

The two studies of the US population conducted by Think Beyond The Pump in collaboration with Stylianos Syropoulos suggest that regardless of such politicization, support for placing climate labels on gas pumps is high, as at least 70 percent support installing the labels. Among republicans the level of support is around 55 percent, whereas it is about 85 percent among democrats.

However, regardless of such high support, Americans underestimate how much support there is for the labels, holding a false social consensus, a general phenomenon known as pluralistic ignorance.[22] In the present case, the perceived support for gas pump labels is about 50 percent.

The two opinion polls before eco-labels were introduced in Sweden found that about 40 percent of the respondents consider it important to get information at the pump about the climate impact and origin of the fuel, whereas around 30 percent think it is not important.[23]

Political support

Not only is the public support for labels significant, but the political support also seems potentially large. The support from Swedish lawmakers for eco-labels on fuel dispensers grew gradually. When Green Mobilists Sweden started its campaign in 2013, there was only one MP from the Left party, Jens Holm, who pursued the issue. Then the interest from the Green party started to grow, with Karolina Skog becoming the main sponsor of eco-labels as a newly appointed Minister for the Environment in 2016. Next, the Centre party stepped in. When the bill was passed in 2018, all eight parties represented in the parliament supported it, from left to right.

In 2016, Vice Mayor Jan Devereux introduced the first bill requiring warning labels on gas pumps in the City Council of Cambridge, MA. The initiative was shot down. In fall 2019 she tried again, and this time the proposal was adopted for further consideration. Jan Devereux did not seek re-election 2020. Therefore, City Councillor Quinton Zondervan took charge of the proposal, and carried it to a successful final vote in the City Council in January 2020 with overwhelming support (Seven yeas, one nay, and one present).

In March 2023, a bill requiring climate and health warning labels on all gas pumps in Hawaii was passed by the State Senate with 22 Ayes, 7 Ayes with reservations, and just 2 Noes. The bill was later blocked by the chair of a House Committee before it was considered on the floor.[24] A similar bill will hopefully be reintroduced in the Hawaii State Legislature in January 2024.

Tentative labelling initiatives

Apart from the ongoing efforts in Hawaii with impressive support in the Senate, gas pump labelling has been considered in several places around the world. Some of these initiatives have stalled and need to be reignited. The more arguments and evidence we find for their effect, the better chance that the labels will spread from Cambridge, MA, and Sweden.

In the city of North Vancouver, an attempt to introduce graphic greenhouse gas warnings on the pumps ended up as lame labels encouraging people to pump the tires, and the like. The graphic warnings were proposed by the campaign group Our Horizon.[25] But the local politicians gave in to the fuel industry, which was allowed to design the final version.[26]

In California, climate and health warning labels on gas pumps have been debated in Berkeley, San Francisco, and Santa Monica. They have also been discussed in Washington State and Massachusetts.

Some European countries have shown interest in Swedish-style eco-labels on fuel dispensers, including Finland, Norway, and Great Britain. Some interest has also been shown by Directorate-General for Climate Action of the European Commission.

According to the original plan, the countries of origin of the fuel’s raw materials would be displayed on the Swedish labels. However, the European Commission complained on legal grounds, and the Swedish government backed down. Nevertheless, in September 2022 the European Parliament adopted a version of the new Renewable Energy Directive that included a requirement that raw materials of biofuels as well as their countries of origin should be disclosed at refuelling stations. However, this requirement was dropped in the final version of the directive. When Russia invaded Ukraine, 26 European NGOs demanded that the country of origin of the crude oil should be disclosed at refuelling stations.[27]

Per Östborn, campaign manager, Green Mobilists Sweden

Contributions by Stylianos Syropoulos, Postdoctoral research fellow, Boston College

[1] Bloomberg, July 19, 2022, Where Are All the Climate Warning Labels on Gas Pumps?

[2] Canadian Cancer Society, October 2021, Cigarette Package health Warnings, International Status Report

[3] The Guardian, December 25, 2020, Massachusetts city to post climate change warning stickers at gas stations

[4] The Guardian, October 1, 2021, Swedish fuel retailers required to display eco-labels at pumps

[5] Gill, M. et al. The BMJ, March 31, 2020, We need health warning labels on points of sale of fossil fuels

[6] Sperling, D. and Gordon, D., Two Billion Cars, Oxford University Press, 2010; Sperling, D. (Ed.), Three Revolutions: Steering Automated, Shared, and Electric Vehicles to a Better Future, Springer, 2018

[7] WHO, Newsroom/Fact sheets, December 19, 2022, Ambient (outdoor) air pollution

[8] Vardavas, C.I., Tobacco Control, Vol. 31, pp. 198-201, 2022, European Tobacco Products Directive (TPD): current impact and future steps

[9] Sambrook Research International, May 18, 2009, A review of the science base to support the development of health warnings for tobacco packages

[10] Gröna Mobilister, Press release, August 15, 2014, Svenska folket vill att drivmedlen ska klimat- och ursprungsmärkas. Vad vill politikerna och bränslebolagen?; Gröna Mobilister, Press release, June 30, 2016, Fortsatt viktigt att få information om drivmedlens klimatpåverkan och ursprung enligt svenska folket

[11] Brooks, J.R. and Ebi, K.L., Global Challenges, Vol. 5, 2000086, 2021, Climate Change Warning Labels on Gas Pumps: The Role of Public Opinion Formation in Climate Change Mitigation Policies

[12] Hammond, D. et al., Tobacco Control, Vol. 15, iii19-iii25, 2006, Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey

[13] Pang, B., et al., BMC Public Health, Vol. 21, 884, 2021, The effectiveness of graphic health warnings on tobacco products: a systematic review on perceived harm and quit intentions

[14] Noar, S.M. et al., Human Communication Research, Vol. 46, pp. 250-272, 2020, Pictorial Cigarette Pack Warnings Increase Some Risk Appraisals But Not Risk Beliefs: A Meta-Analysis; Shadel, W.G., et al., Health Education Research, Vol. 34, 2019, pp. 321–331, Do graphic health warning labels on cigarette packages deter purchases at point-of-sale? An experiment with adult smokers; Strong, D.R., et al., JAMA Network Open, Vol. 4, e2121387, 2021, Effect of Graphic Warning Labels on Cigarette Packs on US Smokers’ Cognitions and Smoking Behavior After 3 Months: A Randomized Clinical Trial

[15] Hughes, J.P., Appetite, Vol. 190, 107026, 2023, Impact of pictorial warning labels on meat meal selection: A randomised experimental study with UK meat consumers

[16] Taufique, K.M.R et al., Nature Climate Change, Vol. 12, pp. 132-140, 2022, Revisiting the promise of carbon labelling

[17] Brooks, J.R. and Ebi, K.L., Global Challenges, Vol. 5, 2000086, 2021, Climate Change Warning Labels on Gas Pumps: The Role of Public Opinion Formation in Climate Change Mitigation Policies

[18] Tankard, M. E. and Paluck, E. L., Social Issues and Policy Review, Vol. 10, pp. 181–211, 2016, Norm perception as a vehicle for social change

[19] Chinn, S., et al., Science Communication, Vol. 42, pp. 112-129, 2020, Politicization and Polarization in Climate Change News Content, 1985-2017

[20] Tyson, A., et al., Pew Research Center, August 9, 2023, What the data says about Americans’ views of climate change

[21] Marlon, J., et al., Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, February 23, 2022, Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2021

[22] Sparkman, G. et al., Nature Communications, Vol. 13, 4779, 2022, Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half

[23] Gröna Mobilister, Press release, August 15, 2014, Svenska folket vill att drivmedlen ska klimat- och ursprungsmärkas. Vad vill politikerna och bränslebolagen?

[24] Gröna Mobilister, April 19, 2023, Hawaii must get its act together – to become the first state with climate change warnings on gas pumps

[25] The Canadian non-profit Our Horizon, founded by Robert Shirkey

[26] The Narwal, October 5, 2016, Climate Change Stickers Designed for Gas Pumps Get Makeover from Canada’s Petroleum Industry

[27] Transport & Environment, March 3, 2022, End imports of Russian Oil to Stop financing Putin’s war: NGOs also demand the country of origin for oil be made clear at petrol stations